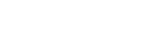

In my recent article, Reimagning Legal Education: Insights from UNH Franklin Pierce’s First 50 Years, I finally wrote down something that I have long said on panels and in discussions with students: That the process of becoming a lawyer can be best characterized by a Venn diagram where three circles only barely grade each other — law school, the bar exam, and then actually learning how to be a lawyer. Upon reflection, my thinking has evolved somewhat. It’s not so much that they barely graze each other; rather, it is that whole diagram is lopsided.

That is, the knowledge and skills necessary to succeed in law school are also somewhat useful for the bar exam, but one could easily graduate from law school without learning everything they need to know to pass most states’ exams, and even that which they do learn is often forgotten by the time the bar exam comes around. As a result, most law school graduates shell out a few thousand bucks for a commercial bar prep course (after having paid $100K+ on law school itself, in many cases). Similarly, most legal education programs do expose students to the basics of practice, but it’s entirely possible for a law graduate to make their way through all three years of law school without ever coming face-to-face with a client — pretend or otherwise. To be sure, schools have gotten better over the years at offering clinical experiences and simulated exercises, but those offerings tend to be considered tangential or “aside” from the core doctrinal offerings of most legal programs.

Although there have been numerous attempts at improving, modernizing, rethinking, reimagining — pick your verb — legal education, those efforts tend to focus on only one of the three circles. Bar passage rates are down among graduates? We’d better add a bar prep course!

True reimagining of legal education requires that we think about the circles holistically, that is, one single circle — a merging of the three — into a single endeavor: becoming a lawyer.

As I see it, there are at least three principal changes that must take place to achieve the overarching goal:

Change the Curriculum

It has become rather cliché for law schools to say that they aim to graduate “practice ready” students, and most schools offer myriad opportunities for hands-on learning, primarily through clinics, externships, legal residencies, and the like. Indeed, the ABA changed its rules about ten years ago to require that students from ABA-approved schools take at least six credits of “experiential” courses. While that’s a good start, I suggest that most of the law school curriculum ought to be practical. While I appreciate the need for some doctrinal instruction, there is no reason why even the traditional doctrinal courses shouldn’t include some measure of practical exercises. A contracts course, for instance, might involve drafting or at least reviewing real contracts to see how the various doctrinal features of the law manifest in practice. A civil procedure course might take on the appearance of a trial advocacy course, at least briefly, and give students an opportunity to brief or perhaps argue a motion.

Beyond the doctrinal core, there is ample room in traditional upper-division offerings to incorporate practical skills. A wills and trusts course could include exercises involving developing an estate plan, for instance. A trademark class might involve pairing students up, with one playing the role of a trademark examiner denying an application for registration, and the other drafting a brief to overcome it. The possibilities are as endless as the practice of law is diverse.

To realize this goal, law schools will need to rethink their approach to hiring faculty.

Change the Faulty

The composition of law school teaching faculty must shift to emphasize practical skills over theoretical knowledge. This will draw some ire, no doubt, but the reality is that most law schools today do not have a faculty that is sufficiently qualified to develop or delivered practice-oriented courses. Although precise figures are elusive, my anecdotal research suggest that most law professors practice for around 3-5 years, often at a “biglaw” firm, giving them only a brief, jaundiced view of the profession. And once they’re in the academy, there is little incentive to maintain or enhance their practical skills, because academic tradition, affirmed by the ABA’s accreditation standards, emphasizes research and faculty governance over teaching, creating an environment more conducive to producing laborious law review articles than practicing lawyers.

Many of the practical courses offered in law schools now are taught by either clinical faculty or adjunct faculty, the latter of whom typically teach on a part-time basis while practicing on a full-time basis. Neither group are particularly well embraced by traditional faculty, who generally see them as being “beneath” the “real” faculty who spend their days thinking grand thoughts about the law, writing about them in publications that other academics read, and participating in academic salons where they congratulate each other for those grand thoughts. Sometimes they teach, too.

As I wrote in my recent article, it’s time to flip the script on the law school pecking order, putting more emphasis on teaching and learning, and less on the academy’s mutual admiration society. Hiring faculty that spend most of their time practicing what they (pr)(t)each exposes students to a “boots on the ground” perspective of the law that is far more realistic, and probably far more useful, than a traditional academic course.

Schools and professors need not abandon “pure” academic pursuits entirely, but I suggest that successful law schools of the future should focus less on them. Perhaps some schools might continue emphasize academics and theory over practice, while others might embrace the practice-focused approach. Let the market decide which are more successful.

Of course, the problem is that we don’t have a free market for legal education. Instead, the market is run by legal education’s drug lord, the American Bar Association Section of Legal Education and Admissions to the Bar, which organizes the cartel of ABA-approved law schools — another one of legal education’s circle jer… mutual admiration societies. Accredited law schools get re-evaluated every ten years by a committee comprised largely of faculty and administrators from other schools, based on outdated and outmoded standards.

Fixing legal education will require, at a minimum, ending the ABA’s monopoly on law school accreditation.

NB: For those thinking that my diatribe above is the product of “sour grapes,” I assure you that it is not. I seriously considered entering the academy a number of years ago, but after attending a few academic conferences, it was clear that it wasn’t the place for me. I actually felt a little ripped off as a then relatively recent graduate, because it became clear how little emphasis law professors placed on teaching (much less teaching practical skills) and frankly, how little many of them even knew about practicing law. It was around that time that I began my first stint as an adjunct instructor at UNH Franklin Pierce, and it became clear that serving as an adjunct gave me the best of both worlds and was the right approach to academics for me.

And the best thing is, even without tenure, I have absolute academic freedom. If the school doesn’t like something I do or say, they can let me go for any time and for essentially any reason (just like grownup jobs), but because teaching’s not my full-time gig, I don’t really need to worry about it. I’d miss teaching, to be sure, but I can pay the bills whether I teach or not.

The moral of the story: You don’t need tenure to assure academic freedom, you just need a real job. But that’s probably a different blog post.

Change the Bar Exam

Perhaps most importantly, to convince law schools and their faculties that it’s time to evolve the model, bar admission authorities must explore new approaches to assessing competence and admitting people into the profession. This will require not only re-evaluating the traditional bar exam for “full lawyers,” but also considering proposals for new categories of licensed legal professionals that would be authorized to perform certain tasks within particular legal domains, such as estate planning, family law, and the like. Such models would open the legal profession to a broader (and hopefully more diverse) slate of practitioners and make commonly requested legal services more accessible to the public.

For “full lawyers,” the bar exam is in desperate need of an overhaul. As I note above, there is very little on the bar exam that resembles what we expect lawyers to do in practice (unless, I suppose, they decide to pursue a life of tutoring students for the bar exam).

There has been some positive movement in this space, as the National Conference of Bar Examiners (NCBE), the not-for-profit entity that publishes the most widely used components of most jurisdictions’ bar exams, saw the writing on the wall and announced, after a seemingly endless parade of studies, public notices, and other “look at how progressive we are” public engagements, the “NextGen Bar Exam” which, says the NCBE, “will test a broad range of foundational lawyering skills, utilizing a focused set of clearly identified fundamental legal concepts and principles needed in today’s practice of law.”

The new exam is supposed to launch in 2026 and as of this writing only 20 jurisdictions have “announce their intent” to adopt (which, I note, is not quite saying the same thing as “they have adopted it”). Neither California nor New York have “announced their intent” to adopt it yet, which is telling, and potentially fatal to the NCBE’s initiative. I’m not entirely convinced that without the scale of these two states, it will be economically feasible for the NCBE to proceed.

This is also an area where getting rid of the ABA, or at least its oversight of the law school accreditation process, would go a long way to improving things. Most jurisdictions require that to even sit for the bar exam, a candidate must have graduated from an ABA-approved law school, cementing the cartel’s role as the gatekeeper.

The most effective thing to do, in my view, is drop the exam entirely and replace it with a comprehensive evaluation of each student’s performance in law school courses which, as noted above should take on a more practice-focused character.

This is essentially what UNH Franklin Pierce’s Daniel Webster Scholar Honors Program has been doing for two decades. Each year the school selects a handful of top students who have applied to participate in a series of intensive, practice-oriented courses, out of which they prepare a portfolio of work which is reviewed by a bar examiner. Upon satisfactory completion of the program, the students are granted admission to the bar without having to take the traditional two-day New Hampshire bar exam.

More states should look at the DWS program as a model, and indeed, a number are. The California State Bar recently undertook a comprehensive examination of the various “pathways to licensure,” including DWS, but concluded that it would be too expensive to implement in a state like California with significantly more bar examinees than New Hampshire.

I disagree, as I describe more fully in my paper, and wholeheartedly believe that programs like DWS should become less remarkable in the future. Instead, they should be come known simply as “law school.”

To be sure, fixing the lopsided Venn diagram will require cooperation and coordination across a broad spectrum of constituencies across the bar admission industrial complex: law schools, state bar associations (and specifically the bar examiners), the American Bar Association Section of Legal Education and Admissions to the Bar, and the National Conference of Bar Examiners. But perhaps most importantly, current practitioners, law firms, and others who employ new law school graduates must begin to acknowledge and recognize that effective legal education today may not look like it did yesterday, and commit to hiring graduates that may not have come through what have become known as the “traditional” channels of bar admission.

Change is possible, but it requires a shift in mindset for both the supply and demand side of the equation.