In 1870, Christopher Columbus Langdell was appointed dean of Harvard Law School, where he was “called upon to deal with was the construction of a new curriculum for the School, divided into first and second year courses.”¹

He did so initially by “appointing eminent lawyers at the bar or bench to give instruction on special subjects in relatively short courses.”² But Langdell was skeptical that success as a legal practitioner would necessarily translate into success as a legal educator.

Rather, “[h]e was inclined to believe that success at the Bar or on the Bench was, in all probability, a disqualification for the functions of the professor of law.”³

Indeed, just several years after taking the helm, Langdell appointed a recent Harvard Law graduate, with no practical experience, to an associate professorship.⁴

Then president Charles W. Elliott supported Langdell’s decision over skepticism by Harvard’s board, noting that “there were parts of professional teaching which young men could do better than old men, even though the young men had had but little professional experience.”⁵

Beyond being taught by young men, a key — and long enduring (to this day, in fact) — feature of the Landgellian classroom is the forensic examination of past judicial opinions, through which students would come to extract the law. As later described by President Elliott, Langdell:

tried to make his students use their own minds logically on given facts, and then to state their reasoning and conclusions correctly in the classroom. He led them to exact reasoning and exposition by first setting an example himself, and then giving them abundant opportunities for putting their own minds into vigorous action, in order, first, that they might gain mental power, and, secondly, that they might hold firmly the information or knowledge they had acquired.⁶

• • •

Today, over 150 years later, the basic structure of U.S. legal education remains much as it did when Langdell “invented” it.

Although it is now a three-year endeavor, most law school graduates (and undoubtedly current third-year students) would agree that the “meat” of the curriculum is in the first and second year, and there remains a proclivity among law school hiring committees for those “young men” (and now even women, believe it or not) who graduated within the past several years and have little more than only a dash of professional experience — and ideally, that experience is limited to a fellowship or legal writing instructor role from an acclaimed institution.

Though experienced practitioners do sometimes slip through into tenure-track roles, it is far more common for the “old [(wo)]men” to be relegated to adjunct positions.

And the classrooms led by those “young men [and women]” approach teaching in more or less the same way they did 150 years ago: asking students to read hundreds of pages of previously decided cases and then quizzing them on the facts and court’s legal reasoning of each, through which the law will reveal itself, and ultimately become implanted in the minds of budding lawyers.

Just how well implanted becomes apparent a couple years after it is first taught, when recent graduates begin studying for the bar exam, usually paying thousands of dollars for a commercial bar preparation course.

• • •

This old model, which relies heavily on memorization of arcane facts and rules, in domain-specific silos, no longer works.

A recent study conducted by the Institute for the Advancement of the American Legal System (IAALS) concluded that some of the most important skills for new lawyers to have involved things like having the ability to understand the “big picture” of a client’s matter, to interact with a client, communicate as a lawyer, identify legal issues, and behave professionally.

Rather than leaving law school with a mental register of largely disjointed, isolated cases and rules, the IAALS study found that most senior lawyers preferred junior lawyers to come to them with an understanding of legal professes and sources of law, an understanding of “threshold concepts” in many subjects, and the ability identify legal issues, conduct legal research, and to pursue self-directed learning.

One survey respondent observed that the best new lawyers are those who “understand the end goal and are thinking broadly as they’re doing the research. For example, maybe [my supervisor] should have actually been asking this question, and here is what she really needs to know about this issue, not just the narrow issue that she asked me about.”⁷

In short, to train lawyers effectively to succeed in the modern legal environment, law schools must embrace a new model — one that considers the curriculum holistically, rather than a series of independent courses, and one that emphasizes practice-focused skills and concepts at its core.

• • •

In my recent article celebrating the 50th anniversary of the University of New Hampshire Franklin Pierce School of Law, I set forth a curriculum framework that attempts to do just that.

Based broadly on constructivist learning theory, which holds that learners construct knowledge by assimilating new experiences with prior knowledge, the framework emphasizes opportunities for learners to “do” law, rather than simply think, write, and talk about it.⁸

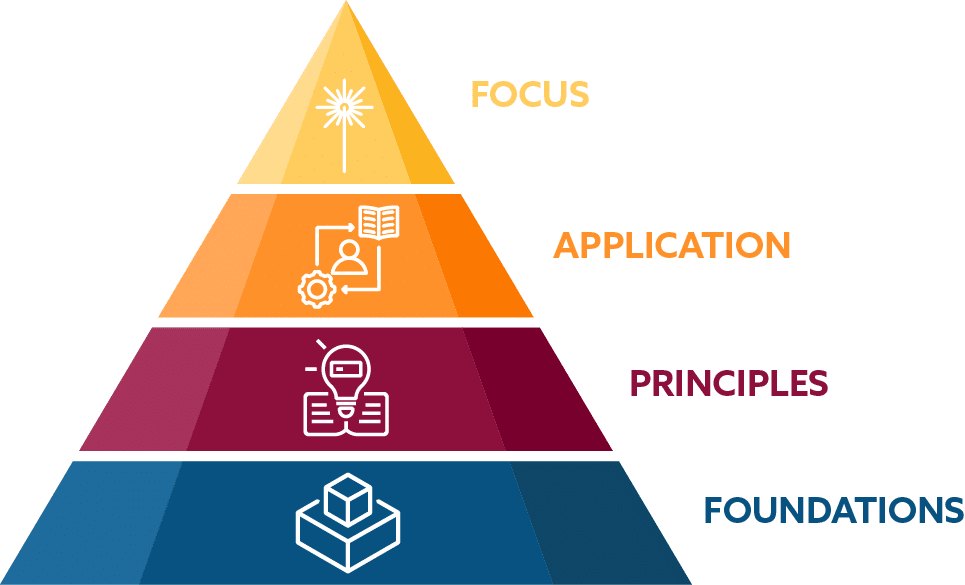

The model comprises four dimensions: foundations, principles, practice (since renamed “application”), and focus.

Let’s look at each in turn:

Foundations

Foundations courses represent the building blocks of successful legal understanding and practice.

These courses comprise a mix of substantive law that undergirds our entire legal system such as constitutional law and the legislative process; fundamental skills necessary for successful legal practice such as legal writing, research, and oral advocacy; and exposure to the various types of work that legal professionals actually do and the environment in which they do it.

Although some law students show up with a sense of the type of practice they want to pursue, many come to the profession with only a general, often poorly informed, idea of what to expect from the legal profession.

A key component of the foundations portion of the curriculum is aimed at helping students think about career path options as early as possible in the process so that they can craft the rest of their legal education in a way that optimizes exposure to the most relevant knowledge and skills.

Principles

Principles courses are those that look most like today’s traditional law school offerings — the “standard issue” doctrinal offerings that cut across a broad swath of practice areas, including business associations, contracts, civil procedure, criminal law and procedure, evidence, property, torts, wills and trusts, and the like.

While these courses are traditionally offered in fairly predictable ways — readings, lectures, and an exam or two — there is rich opportunity in this area to reimagine how we teach certain topics.

Although primarily focused on delivering doctrinal principles, there is no reason why those cannot be taught through the use of real-world examples and materials in addition to (or in some cases, instead of) traditional cases and the overpriced textbooks comprised of them.

A course on civil procedure, for instance, might use real court filings to illustrate the lifecycle of a lawsuit (bonus points students can attend a real hearing at a nearby courthouse). Depending on the nature and complexity of the case, that might be a useful way to teach certain torts or contracts principles as well. A contracts course might use a real agreement taken from a public company’s SEC filings.

Similarly, instructors might consider developing principles courses around one or more fictitious-but-realistic case files, akin to what students may encounter on the Multistate Performance Test (or the various state-specific equivalents), where they are asked to perform a particular task based on a library of appropriate materials (e.g., cases, deposition transcripts, a set of instructions).

Application

Application courses are built around exercises that put learners into the role of junior attorneys, giving them opportunities to “do lawyer things,” as opposed to reading cases or listening to professors pontificate — courses on contract drafting or licensing in specific fields, litigation practice in a particular discipline, or judicial opinion drafting, for instance.

These courses are where students will be exposed to the interrelationships between disciplines that they have learned about in their foundations and principles courses, something that is sorely missing from traditional legal education.

Case in point: I took the California bar exam just a few years ago, following nearly 20 years of practicing in other jurisdictions and under California’s “registered in-house counsel” program. In preparation, I joined a Facebook group for prospective examinees, where one of the parlor games was to guess which topics would appear on the upcoming exam, in part, by looking at trends from past exams. Many were stunned to learn that in some past exams, a single question might test multiple doctrinal areas of law, such as contracts and remedies, or civil procedure and evidence.

Of course, to those of us with years of practice under our belt, the combinations seem entirely logical.

Indeed, the more sadistic of us could probably come up with some decent questions that incorporate most, if not all, of the topics tested on the bar exam.⁹

But because we traditionally have taught the topics in disparate silos, with little attempt at showing connections between them, it is hardly surprising that bar examinees taking the exam straight out of law school would not necessarily see those interrelationships.

Because legal issues rarely present themselves in discrete, doctrine-specific packages, understanding the interrelationships between disparate areas of law is a touchstone of a successful legal practice.

Traditional legal education leaves students with the building blocks to construct a resolution, but the application courses in my framework give them a set of construction drawings and mortar.

Focus

Focus classes, at the top of the pyramid, “fine tune” the student’s knowledge and skills to address specific needs and interests.

These courses are intended to be relatively short (one credit at most), narrow, and as the name suggests, focused on specific issues, topics, current events, industries, or detailed areas of practice.

They are, essentially, mini capstone courses that allow students to experience how various threads of foundations, principles, and applications courses get woven into very specific contexts.

For instance, in 2015, at the height of the “deflategate” scandal that plagued the New England Patriots and its storied quarterback Tom Brady, UNH Franklin Pierce professor and accomplished sports journalist Michael McCann developed a course titled “Deflategate: The Intersection of Sports, Law and Journalism.”

According to its syllabus, students learned about “crucial areas of law that relate to sports and the methodologies used to practice in relevant fields” such as contract law, business law, constitutional law, intellectual property, evidence, torts, labor law, and antitrust.

Another example: During the Spring 2020 semester, as the COVID-19 pandemic forced instruction online, Professors Scott Schumacher and Zahr Said at the University of Washington created “Law in the Time of COVID-19” to “address the special circumstances unfolding in real-time,” covering areas such as immigration, health care, technology and innovation policy, and “what it means to provide legal services remotely and a time of crisis.”

Is it likely that any of the students in Prof. McCann’s course will become ensnared in a football scandal, or cover one for a national sports news outfit?

Will any of Prof. Said or Prof. Schumacher’s students will have to navigate another global pandemic?

It’s possible, I suppose, but relatively unlikely. The importance of these courses is not that they convey “the law,” per se, but rather but that they tie real-world, lived experiences to the material that learners have obtained through other offerings, giving learners valuable insight into how legal practitioners accommodate real-world challenges.

And because these courses call upon learners to assimilate new knowledge and skills with their existing understanding of the world, they serve as powerful learning opportunities.

“But What About…”

Some Thoughts on Anticipated Objections

Who’s Going to Teach All These Classes?

In my ideal world, much of the law school experience would be directed by practicing lawyers who moonlight as adjunct professors. That is not to suggest that all practicing lawyers are necessarily good instructors, nor is it to suggest that we should do away entirely with full-time academic faculty, but I do believe law schools should endeavor to expose students to more practitioner-led experiences as they move “up the pyramid” from their foundations courses into the other dimensions.

Would Students Have the Knowledge Necessary to Pass the Bar?

My framework is just that — a framework, or a way of organizing legal instruction. It stops short of prescribing specific courses, topics, and skills that those courses must cover, though as you can see from my descriptions above, I have a general idea of how I would structure those courses within the framework.

A law school administrator keen on following the model but developing a program that focuses primarily on teaching bar-tested topics and skills necessary to pass the bar could do so, but I personally would not recommend it.

Passing the bar is a necessary but not sufficient condition of becoming a lawyer, but because of the America Bar Association’s accreditation standards and disclosure rules, the U.S. News & World Report Rankings, and general public shaming, many law schools put outsized emphasis on increasing their graduates’ bar passage rates by offering and encouraging students to take more “bar classes.”

But as I have written about elsewhere, the bar exam is not about practicing law, and most students take a commercial bar prep course anyway. The time spent in law school would be best used training students how to be lawyers, rather than how to memorize facts and test-taking techniques that will have little value after the bar exam.

Would This Model Comport with the ABA Standards?

Probably not.

My model emphasizes real-world practical skills and learning, but the ABA standards emphasize the number of full-time faculty writing law review articles and the size of the library.

Until the ABA either changes its tune, or someone upsets the de facto monopoly that it currently has over law school accreditation, there will be little room for innovation outside of those states where a law school graduates do not necessarily need an ABA-accredited law degree to sit for the bar exam. Alas.

Let Me Have It

I want to hear from you — especially if you’ve been through law school. Am I spot-on or way off base? Is this framework too bold, not bold enough, or just plain wrong? What hits the mark, and what completely misses it? Tell me what you think — and don’t hold back!

References & Notes

¹ Charles W. Eliot, Langdell and the Law School, 33 Harv. L. Rev. 518, 520 (1920).

² Id.

³ Id.

⁴ Id.

⁵ Id. at 521.

⁶ Id. at 523.

⁷ Institute for the Advancement of the American Legal System, Building a Better Bar: The Twelve Building Blocks of Minimum Competence 47 (2020).

⁸ Interestingly (to me anyway), the Langdellian model is arguably a constructivist-based framework as well, but with a different objective than mine. As a result, each emphasizes doing different things. My model is aimed at developing practical lawyering skills, and so its structure is built to maximize opportunities to practice those skills. Landgell believed that law school should prepare students to be legal scholars, which is, of course, exactly what his case method of teaching aims to let students do: think and talk about the law, but not necessarily practice it.

⁹ As of this writing (January 2025), those are: business associations, civil procedure, community property, constitutional law, contracts, criminal law and procedure, evidence, professional responsibility, real property, remedies, torts, trusts, and wills and succession.